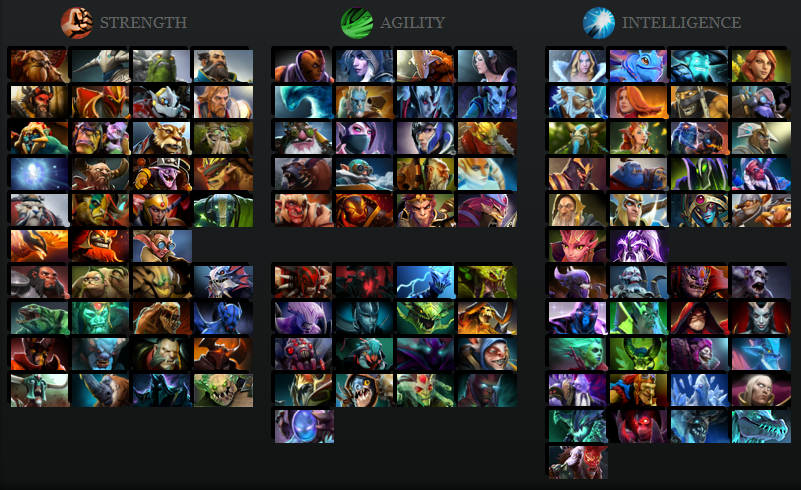

In this post, I will introduce the strategy pattern and factory patterns using Dota2 Heroes as examples. Dota2 is a multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) video game, a sequel to Defense of the Ancients (DotA), played in matches between two teams of 5 players. Each player independently controls a powerful character, known as a “hero”, with unique abilities and roles.

See code at Github repo (https://github.com/yangju2011/design-patterns).

Table of Contents

Strategy Pattern

Definition

- Defines a family of algorithms, encapsulates each one, and makes them interchangeable.

- Lets the algorithms vary independently from clients that use it.

Code example

In this example, we will build a Character simulator of Dota2 Characters. Dota 2 is played in matches between two teams of 5 players. Each player independently controls a powerful character, known as a “hero”, with unique abilities and roles. There are other characters in Dota2 such as couriers that transport items from shops to heroes, and shop sellers from whom heroes can buy items. Each character (hero, courier, seller) exhibits different behaviors and attributes.

Character is an abstract class that has 2 behaviors to be initialized: MoveBehavior and AttackBebavior. It also 6 methods: move, attack, display, disable, setMoveBehavior, setAttackBehavior.

There are various concrete Character classes: SvenCharacter, SniperCharacter, CrystalMaidenCharacter, CourierCharacter, SellerCharacter that extends Character. These concrete classes have different behaviors.

Note that MoveBehavior and AttackBebavior are interface which encapsulates different types of behaviors.

Output:

...Displaying I'm Sven! My primary attribute is Strength I have melee attack! I move! I can disable! ...Displaying I'm Sniper! My primary attribute is Agility I have ranged attack! I move! ...Displaying I'm Crystal Maiden! My primary attribute is Intelligence I have ranged attack! I move! I can disable! -- set move behavior I move at a speed burst! ...Displaying I'm Courier! <attack-not-available> I move! -- set move behavior I move at a speed burst! -- set attack behavior I have ranged attack! ...Displaying I'm Seller! <attack-not-available> I do not move!

Factory Pattern

Definition

Simple Factory: not actually a design pattern, but more of a programming idiom. It encapsulates the create method for object creation.

Factory Method: defines an interface for creating an object, and lets subclasses decide which class to instantiate.

Abstract Factory: provides an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete class

1. HeroSelector with Simple Factory

In this example, we want to build a HeroSelector that takes a selection of hero name in String, and print out some information about a selected hero.

In this example, we want to build a HeroSelector that takes a selection of hero name in String, and print out some information about a selected hero.

A straightforward implementation is HeroSelector which contains a selectHero method:

public Hero selectHero(String heroName){

... return hero;

}

This method includes conditional statement to instantiate various Hero objects:

if (heroName == "sven"){

hero = new SvenHero();

}

else if (heroName == "sniper"){

hero = new SniperHero();

}

...

There is also additional code to print out behaviors of a selected hero:

hero.load();

hero.render();

hero.display();

If we have new hero names, we will need to modify the conditional statements in HeroSelector, while the code about hero behaviors remains unchanged.

As the code shows, we know what is varying (object creation with new) and what isn’t (printing hero behaviors), so it is probably time to encapsulate the varying part.

We can use Factory to encapsulate the details of object creation, and move the conditional statements to a separate class SimpleHeroFactory, which contains createHero method.

public Hero createHero(String heroName){

return hero;

}

The HeroSelectorWithSimpleFactory gets SimpleHeroFactory passed to its constructor:

public HeroSelectorWithSimpleFactory(SimpleHeroFactory factory){

this.factory = factory;

}

The selectHero method uses the factory to create a concrete hero object:

hero = factory.createHero(heroName);

createHero can be defined as a static method, as in SimpleHeroFactoryStatic. With a static method, we do not need to instantiate an object to use the create method as shown in HeroSelectorWithSimpleFactoryStatic.

By encapsulating the createHero method in SimpleHeroFactory, we decouple object creation from how an object is used. In this example, the object Hero created from SimpleHeroFactory is used in selectHero. There can be other classes that use the factory to get Hero for its properties and behaviors. By using Factory, we have only one place to make modifications when the implementation of createHero changes.

Output example:

...Loading hero from database Hero name: Crystal Maiden Hero attribute: Intelligence Hero position: Hard Support Hero abilities: Crystal Nova Frostbite Arcane Aura Freezing Field ...Rendering ...Displaying I'm Crystal Maiden! -- Selected hero Crystal Maiden

2. HeroSelector with Factory Method

Say we have two types of clients (users): paid subscription –

Say we have two types of clients (users): paid subscription – Dota Plus, and unpaid – Regular. The two clients will create slighly different Hero objects when selecting a heroName. For example, Dota Plus may have additional tags [Dota Plus] for hero’s name and abilities.

Regular Crystal Maiden:

public CrystalMaidenHero(){

name = "Crystal Maiden";

attribute = "Intelligence";

position = "Hard Support";

abilities.add("Crystal Nova");

abilities.add("Frostbite");

abilities.add("Arcane Aura");

abilities.add("Freezing Field");

}

Dota Plus Crystal Maiden:

public DotaPlusCrystalMaidenHero(){

name = "[Dota Plus] Crystal Maiden";

attribute = "Intelligence";

position = "Hard Support";

abilities.add("[Dota Plus] Crystal Nova");

abilities.add("[Dota Plus] Frostbite");

abilities.add("[Dota Plus] Arcane Aura");

abilities.add("[Dota Plus] Freezing Field");

extraVoiceLines.add("I've got goosebumps!");

extraVoiceLines.add("Is it cold in here or is it just me?");

}

In this case, we make createHero an abstract method in original HeroSelector client, and then create HeroSelector subclasses for each different types of clients with their correponding createHero implementation. This is called the Factory Method pattern.

Factory method lets the subclass decide which class to instantiate at run time. The Creator class can be written without knowledge of the actual Product that will be created.

Output example:

...Loading hero from database Hero name: [Dota Plus] Crystal Maiden Hero attribute: Intelligence Hero position: Hard Support Hero abilities: [Dota Plus] Crystal Nova [Dota Plus] Frostbite [Dota Plus] Arcane Aura [Dota Plus] Freezing Field Extra voice lines: I've got goosebumps! Is it cold in here or is it just me? ...Rendering ...Displaying [Dota Plus] I'm Crystal Maiden! My primary attribute is Intelligence -- Selected hero [Dota Plus] Crystal Maiden

It is easy to accommodate new changes when there is a new implementation for the factory method.

In heroFactoryMethodV2, we have a new client BattlePassHeroSelector which creates new types of Heros with the [Battle Pass] tag.

Battle Pass Crystal Maiden:

public BattlePassCrystalMaidenHero(){

name = "[Battle Pass] Crystal Maiden";

attribute = "Intelligence";

position = "Hard Support";

abilities.add("[Battle Pass] Crystal Nova");

abilities.add("[Battle Pass] Frostbite");

abilities.add("[Battle Pass] Arcane Aura");

abilities.add("[Battle Pass] Freezing Field");

extraVoiceLines.add("I've got goosebumps!");

extraVoiceLines.add("Is it cold in here or is it just me?");

}

public class BattlePassHeroSelector extends HeroSelector {

public Hero createHero(String heroName){

3. HeroSelector with Abstract Factory

Note that a

Note that a Hero may have arbitrarily defined properties such as position. But in reality, we may want to ensure consistency in a Hero’s properties. For example, we may only allow the client to select among a set of predefined values for position, weapon and boots.

In this example, we are building a Hero with different roles: Carry and Support. Each role uses one set of HeroBuild that include family of objects such as Position, Boots, Weapon, and a list of Item.

public abstract class Hero {

public String name;

public Position position;

public Boots boots;

public Weapon weapon;

public ArrayList<Item> startItems;

}

public interface HeroBuildFactory {

Position createPosition();

ArrayList<Item> createStartItems();

Boots createBoosts();

Weapon createWeapon();

}

We then implement createMethod in concrete HeroBuildFactory classes for Carry and Support:

public class CarryHeroBuildFactory implements HeroBuildFactory {

@Override

public Position createPosition() {

return new SafeLanePosition();

}

...

}

public class SupportHeroBuildFactory implements HeroBuildFactory {

@Override

public Position createPosition() {

return new HardSupportPosition();

}

...

}

The concrete HeroBuildFactory uses Factory Method to instantiate a family of objects for each HeroBuild.

Output example:

...Loading hero from database ...Rendering ...Displaying I have a build with boots! ...Selected Hero Build ---- Support Build with Boots ---- Position: Hard Support With boots: Tranquil Boots With start items: Tango, Observer Ward, Clarity

Note

When we use Factory Method or Abstract Factory pattern, we end up creating a lot more classes and files to encapsulate what varies, program to interface, and make our classes open for extension but closed for modification – all of these are OO principles. In practice, we need to weigh the benefits of clean code and the added work of creating and maintaining various classes.